How Fierce Convictions Led to Amazing Grace

Introducing our next mini-comic series, following the stories of William Wilberforce and Hannah More

I first heard of Wilberforce in 1984 when the pastor of my church in Pittsburgh, The Rev. John Guest, gave a sermon about him after reading God’s Politician, a biography which I promptly bought and have never put down. As I entered the Masters of Arts and Religion program at Trinity Seminary a few years later to focus on “public square theology,” Wilberforce and the Clapham community were a north star and an aspiration. Rubber met the road when I oversaw the longshot challenger Congressional race of Rick Santorum in 1990, and after a surprise victory, came to Capitol Hill as his Chief of Staff to practice what I had been planning to preach.

For the next 16 years, until I left in the Hill in 2007, Clapham and Wilberforce were constant vocational companions and counselors. I then started my firm, The Clapham Group, to embody the principles of their work and contextualize it to the 21st c. American public square.

For those of you who don’t know much about Hannah More and William Wilberforce, and why we are named after the group that they were a part of, the Clapham Sect, consider this a contribution to Salt and Light a little crash-course — and for those who do know something about them already, maybe this will be a little refresher.

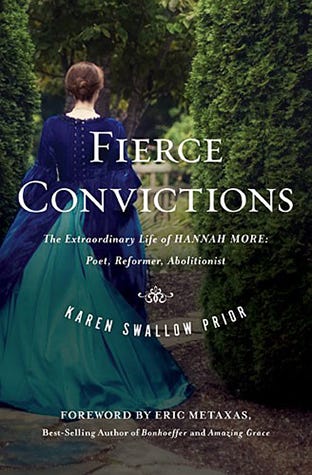

Clapham Group’s first client, the film Amazing Grace (2007), tells the story of William Wilberforce and his fight to end slavery, the release of which coincided with the 200th anniversary of the British Parliament voting to end the slave trade. Eric Metaxas wrote a new biography of Wilberforce, published concurrently with the film and bearing the same title (2007). Hannah More also played a unique and crucial role in the fight to end slavery. Karen Swallow Prior, a friend of The Clapham Group, wrote an important new biography of Hannah More aptly titled Fierce Convictions (2014). We have a lot to learn from both the causes that they championed and, just as importantly, the way they campaigned for these causes.

Hannah More, a force to be reckoned with in and of herself — despite being a single woman in Georgian England — had just as much influence as Wilberforce when it came to fighting for the abolition of the slave trade and slavery itself, at least in Great Britain and her colonies. The story of their lives, and those of the many other influential figures they labored with, needs to be told again and again in each generation, in order that we do not forget both the end result of their contribution to liberty and true virtue, and also the way they went about achieving those ends.

More and Wilberforce worked closely together on Wilberforce’s two 'great objects’ for many years. Surrounding themselves with other like-minded co-belligerents such as Thomas Clarkson, Henry Thornton, John Newton, Granville Sharpe, Josiah Wedgwood, William Cowper, and Henry Venn, they labored for many years to abolish slavery and reform the manners (what we would call morals, in today’s parlance) of both the upper and lower classes. Both of these worthy goals had deeply spiritual and religious undertones for More, Wilberforce, and their cohort. They each underwent a deepening of their nominal Christian faith before undertaking these causes and continued to grow in their faith as they labored together for many years. Neither of them would have achieved as much as they did apart from each other nor apart from their faith in Christ.

Hannah More grew up one of five daughters of a school teacher father (hardly very noble beginnings). Having a father for a teacher did have one major advantage, though, especially because at the time British society did not consider education for girls and women, outside of being trained in the ‘domestic arts’ (i.e. how to run a household), neither suitable nor worth pursuing. More’s father educated all of his daughters alongside his other pupils. The five sisters went on to start their own school for girls, which they ran successfully for more than 30 years. Perhaps because of this early exposure to a well-rounded education, More maintained a love of learning, and in particular the written word (both reading and writing it herself), for the rest of her life.

William Wilberforce’s father died when he was just nine years old, and when his mother struggled to cope with the loss and raise her son by herself, Wilberforce was taken in and raised by his religiously devout aunt and uncle (i.e. they had deep conviction, not just a nominal faith). Over time, as he grew up and attended various levels of schooling, he strayed from this early foundation in the Christian faith. Wilberforce experienced a re-awakening to a deeper spiritual conviction when, as a young man, he took a trip with a friend and tutor from Cambridge University who also happened to be a devout Christian. On their journey, they read Philip Doddridge’s The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. The trip and the book renewed in Wilberforce the spiritual conviction of his childhood. In 1785 Wilberforce sought the council of John Newton in a secret meeting, during which Newton persuaded Wilberforce that he could stay in politics and serve God, if only he could focus on a worthwhile aim — this focus became his two ‘great objects.’

More and Wilberforce met in Bath in the autumn of 1787. They would remain friends and labor together for important causes the rest of their lives, dying within mere weeks of each other, although More was 14 years his senior. Not only did their religious faith sustain More and Wilberforce and their co-belligerents in their long efforts but, just as importantly, a strength of a moral imagination carried them through many years of long, hard fighting to finally achieve the long-sought-after goal of the abolition of the slave trade, as well as abolishing slavery itself years later in 1833. More and Wilberforce knew, as Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote in 1821, that, “[t]he great instrument of moral good is the imagination.” Just as we at The Clapham Group know the importance of utilizing and harnessing the power of imagination — whether it be through films or music or graphic novels — the members of the Clapham Sect knew that creating and promoting good art, art that implicates the viewer and reader, can go a long way to achieving the noble ends to which you are striving.

So what exactly have we learned after nearly two decades of “doing”?

We have learned that Wilberforce and More shared in a community of both conviction and prayer. The “Clapham Sect” that they were both a part of and instrumental in founding and maintaining had mutually upheld and shared convictions that enabled them to encourage each other. They also prayed, both individually and collectively (formally in church settings and informally in homes), which helped them to both clarify and maintain their shared convictions and beliefs on the key issues of their day that they felt passionate about and fought for.

We have also learned that they were deeply committed to and transformed by the Gospel. They knew that they had to believe in their hearts and souls that what they were fighting for was rooted in Christ’s teachings, and that those teachings would carry them through and inspire them in their hard work. Not only were they personally transformed by the Gospel, but they believed that the Gospel could and would transform others’ lives as well, and that true change would start there. At the same time, they were willing to work with others who did not share their same personal convictions, when they had mutually agreed upon goals and means with which to achieve those goals.

In addition, we have learned to follow their example of a holistic approach. They did not “put all their eggs in one basket,” so to speak. They knew that achieving the goals they had would mean trying different methods and approaches. For example, Wilberforce used his presence and influence in Parliament (he was known as a skilled orator) to try to change the laws of the land. More and other writers and artists used their artistic and literary skills to try to persuade people by igniting their imagination. Wilberforce and More came to respect and appreciate the different approaches that each took to the same issues that they were equally passionate about. Similarly, each person involved in the Clapham Sect brought a unique set of skills and dispositions to the community that enhanced their ability to achieve the noble goals that they had set for themselves.

As St Paul reminds us, “For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ….For the body does not consist of one member but of many….But God has so composed the body, giving greater honor to the part that lacked it, that there may be no division in the body, but that the members may have the same care for one another.” (1 Cor 12:12, 14, 24-26)

So, for us at The Clapham Group we have learned some very important lessons from the likes of William Wilberforce, Hannah More, and their cohort at the original “Clapham group,” lessons that we try to emulate and perpetuate: share conviction in community, take a holistic approach to the issues that we face and the problems that we are trying to solve, and be transformed by the Gospel of Jesus Christ and his Church that is at the heart of what we believe and how we live our lives.

Emily Mitchell