The Reformation of Manners

Mark Rodgers and award winning author Kevin Belmonte reflect on Hannah More and "the reformation of manners."

This week, the fourth page of our latest comic, Wilberforce’s Two Great Objects, delves into Wilberforce’s second great objective: the 'Reformation of Manners.'

In this continuation of Mark Rodgers’ interview with author Kevin Belmonte, we’ll explore what the 'Reformation of Manners' meant to Wilberforce—and what it means for us today.

Mark Rodgers

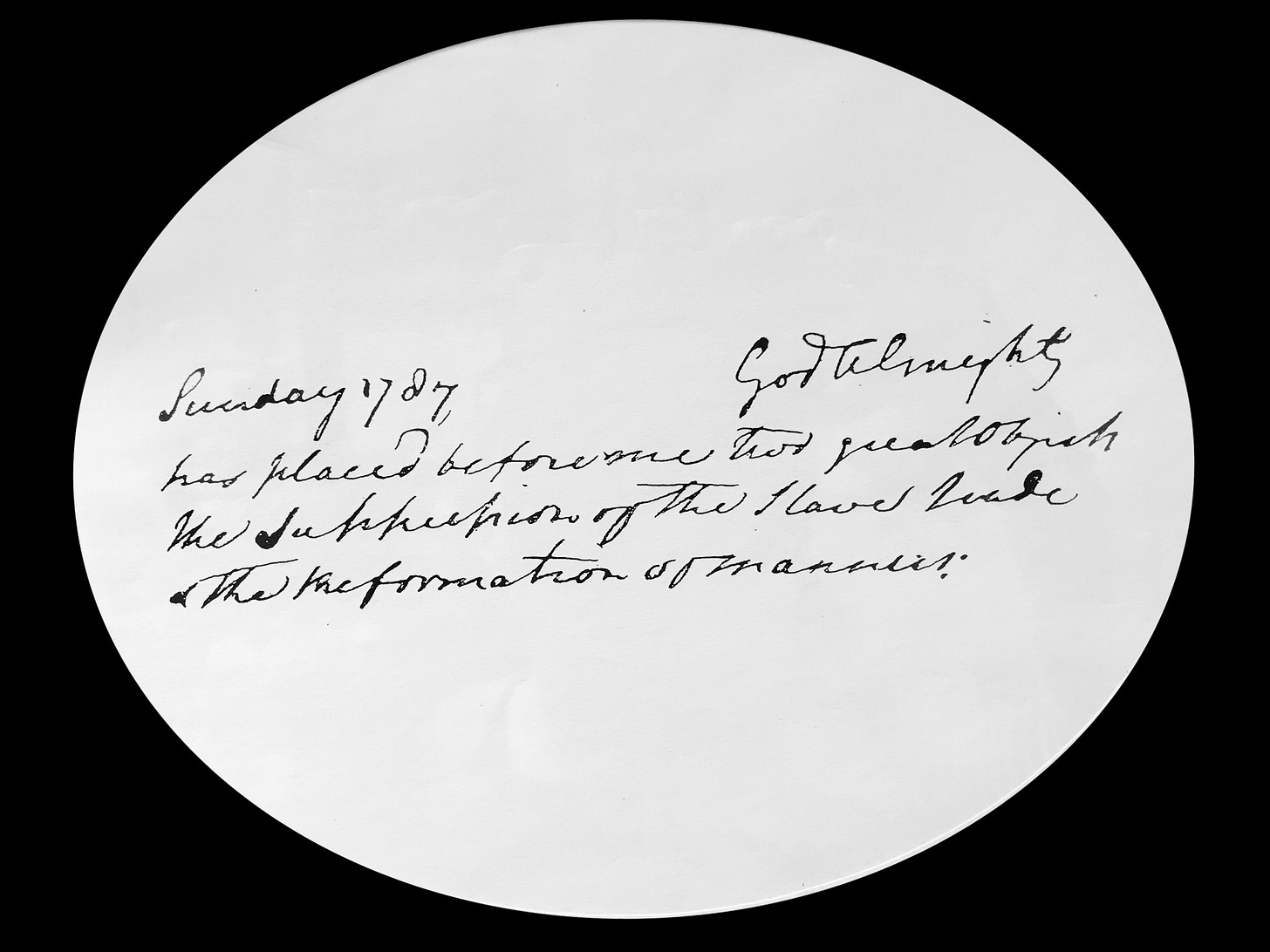

I'm going to move to the second great object for a second here with you- the reformation of manners. Wilberforce wrote “God has placed before me two great objects: the end of the slave trade and the reformation of manners,” [but] that phrase is very foreign to Americans. ‘Reformation of manners,’ it sounds like we're talking about white gloves and tea pots and kind of very kind of Victorian formality. I have above me here a sermon given before the Society for the Reformation of Manners that's dated 1707. This is something that had been around in terms of lexicon in the British society for years. Can you explain, what did they mean by reformation of manners? What was that great object?

Kevin Belmonte

We have to translate and find a bridge back into that earlier time. It's really the work of cultural renewal, born of moral reform and Wilberforce. He's like you and I. He read books that maybe he could get a clue from about how to move forward with some of these things he was hoping to do. Very early on, he read Josiah Woodward's book on the reformation of manners, and he saw that when it was published in 1692, that they'd had more success then, because they were able to branch out not only from a center of activity, but to local reformed societies.

It had the imprimatur of the King. I think it was William and Mary at that time, if memory serves. So with the Royal backing and support and encouragement, there had been something that had done a great deal of good, and Wilberforce was doing what we ought to do in our own time, looking back for historical models – he was no different than you or I. He looked back, he saw this, [and thought] “okay, I can take that and run with it.” And just remember the work of the Reformation of Manners is the shorthand for moral and cultural renewal. That's a way we can think about it.

But I remember when we were struggling with that in the film, how do we get that point across in the script? That's hard. And I was talking with Mike Flaherty, whom, you know well, the President of Walden media, who was so integral to getting that film made. And I was reviewing scripts, I remember there was one window of time I had to write 227-page memos on the script in a couple of weeks, just go over it with a fine tooth comb. And so Mike and I were going back and forth by email about moral renewal. He was worried that that second object would get lost in the film.

And so I just started speaking, thinking aloud, really saying, you know, every time we open a school or a lending library, establish a soup kitchen in the inner city in London, the ball is moved forward, it’s an incremental approach. And I just thought it was one of those things where I was just sort of dashing off a stream-of-consciousness thought. But Mike zeroed in. That's it. People can understand that – that an outgrowth of faith leads you to establish lending libraries or schools or soup kitchens, any one of a number of things which can foster moral and cultural renewal. And so that ended up making it into the movie.

I mean, I don't have a screenwriting credit, but we were watching the film out in LA – Mike and I, we saw an early screening at 20th Century Fox, and he goes, “Do you remember when you wrote that?” He said, “it's in the movie.” So, you know, it's funny. Yeah, we do have to be creative. I think, as people like you and me, if we think history has value, yeah, it's worth looking back trying to understand how those who have gone before have made a difference for good. I think there's sometimes a rolling up your sleeves aspect where you have to try and translate, help people understand what these slightly foreign turns of phrase really meant, and how they're really no different from things we seek to do at our own time. So there you have it.

Mark Rodgers

Yeah, Kevin, I'm going to talk about the social kind of movement building they undertook, which I think you've already pointed out, was multifaceted. So, the creation of societies, certainly the attention to spiritual conversion, right? And spiritual disciplines. They saw, like the Wesley’s did, ultimately the importance of reforms coming from the reformation of the soul and the heart first. Although they recruited people who didn't share their kind of enthusiastic faith, you know, to pursue the issues they worked on.

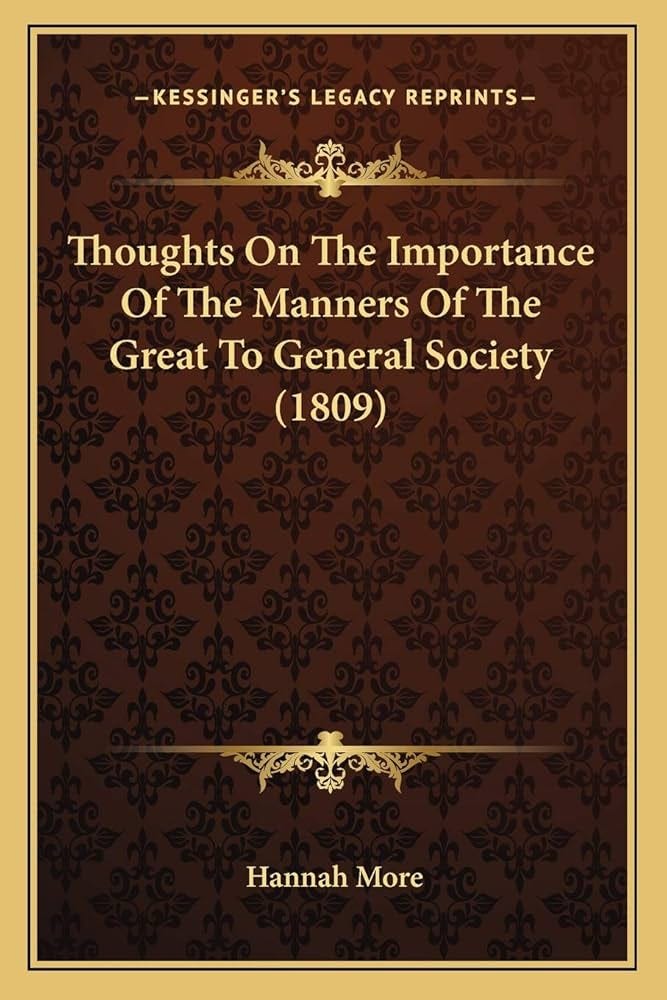

And one of those kind of theories of social change, if you would, I think Hannah singles out, is what I wanted to get your reflections on. So, just about a year after that diary entry of Wilberforce’s, Hannah produced a very small book called Manners of the Great. And in that book, she talks about reformation of manners. It's a kind of an appeal to the elites to live up to their station of society and their obligations, you know, within Christendom, in a sense, and even again, not as not exclusively a religious appeal, although there's an element to that in the book, but in it she says, as she appeals to them, reformation of manners must begin with the great or it will never be effectual.

Their example is the fountain from whence the vulgar or the masses draw their habits and their actions and their character. And I just think that's such a powerful insight in terms of the role of the elites in society in shaping morals of society. Could you just chat about how do we apply that to today? What does that theory of social change look like in today's context? And what way do the elites play [a role] in shaping our society today in America?

Kevin Belmonte

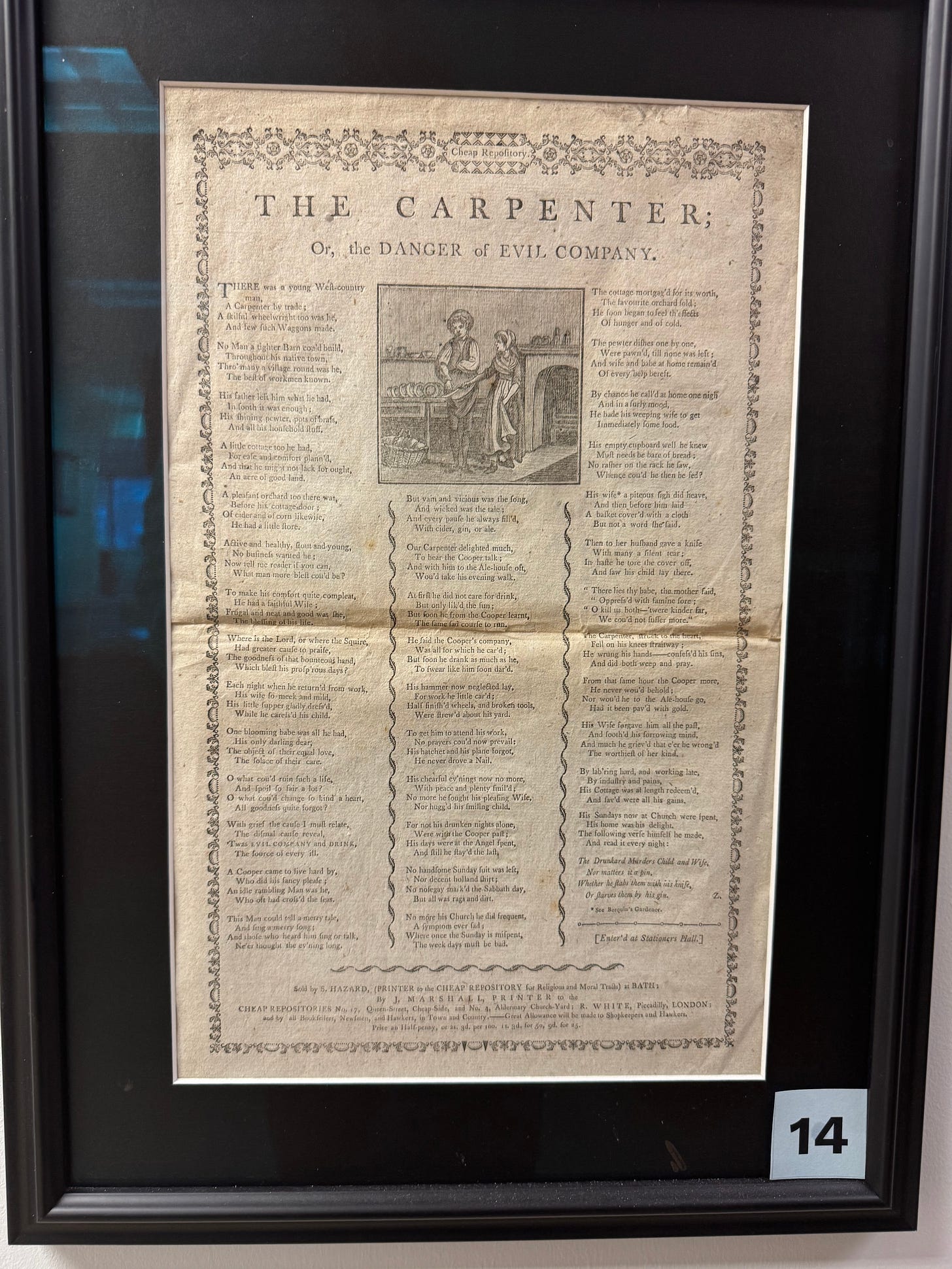

Well, I think, Mark, she understood celebrity culture, although she wouldn't use that phrase, of course, that's something. That's a modern term, but she knew because you had, in lieu of something like television and radio, which wouldn't be invented for hundreds of years, you had prints, you had newspapers, you had checkbooks, you had tracts, like the repository tracts. Literacy was fairly widespread in some pockets in the UK, but chat books, for example, would use wood cuts. It's almost like the stained glass windows in churches, which would tell the Gospel story in ways that the illiterate could understand. They would see scenes pictured for them.

And I think she knew, because the stories of the wealthy, the famous, the accomplished, were things that captivated the public imagination in her own time, that if you could tap into that, realize that that's a part of the culture people look up to people who are prominent, people who are being talked about via word of mouth. If you can tap into that celebrity culture, understand it. See what opportunities are there for her with her book on reform, reformation of the manners of the great, she cared about the social set that she moved in. So, first of all, it was an act of kindness and compassion, wishing to commend faith to members of her own high social circle.

But I think she also understood that she could help them to understand that they could be agents of change, even if they weren't people of faith, that notion of noblesse oblige, which is a wonderful phrase that we need to recover, it's very scriptural to whom much is given, much is required. You don't have to be a person of faith to subscribe to that, to realize that you've been given, perhaps wealth, perhaps opportunities, perhaps you have an estate with tenant farmers. I mean, gosh, there are all kinds of opportunities in that time where, if you were privileged, you could be in a position to do great good.

She was in that position, she said, “Look, I'm going to try and walk out what I'm commending here, and I'll tell you about some of the things that I'm doing, but maybe here's a template for some of you to think intentionally, whether you're a person of faith or no, about fostering the good society. And that was something that was very much in the ether of that time. It was an enlightenment concept, fostering the good society, but it was something where it was complimentary to things that were Christian in nature, too. So, there were ways for these cultural streams to converge. And I think she was just simply casting about for creative, novel ways to speak to the culture of her time and try to make a difference in those settings.

Thanks for reading this week’s excerpt of the interview between author Kevin Belmonte and Mark Rodgers! Stay tuned on Wednesdays for a new comic book page, and Fridays for more excerpts from this interview.